I had done a little research and reading on the area in preparation, but didn’t know what I was in for on one of the farm bus tour stops as part of UMES Extension’s Small Farm Conference. After carefully traversing the winding, backcountry roads to San Domingo, I arrived early at the 38-acre property of Newell Quinton. I parked and went in the direction of a campfire burning, where I found the proprietor stoking a fire with a pitchfork beneath four cast iron pots. Growing up on a dairy farm in Dorchester County, I recognized these pots. My siblings and I used one to put dry ice in for Halloween parties, resembling the perfect witches’ pot. These, however, were being used for their original purpose—making homemade scrapple.

Quinton and his extended family had been tending the fire since 9 that morning and had started the age-old process that would come to fruition around 1 p.m., in time to demonstrate the final touches and pour the concoction into aluminum loaf pans for tour participants to take home and sample. “Everything goes in, nothing is wasted,” he said. “It’ll be done when it holds that paddle (inherited from his mother and approximately 100-years-old).” In San Domingo, making scrapple is a fall tradition around Thanksgiving that has diminished throughout the years.

“We had close-knit families out here,” said Quinton. “Everyone used to raise hogs and get together to make sausage and scrapple. If there was smoke rising early in the morning, you knew someone was getting ready to make it and everyone went down to help.”

After a career in the federal government that took him to the Western Shore, Quinton came back to retire in the area. “This is home,” he said. “Kids today have no idea how their parents and grandparents lived and the importance of community. It’s important to know how people shared what they had and helped each other. I don’t know that we do that enough today.”

Quinton has been an advocate for the San Domingo community and for reviving old traditions. “It’s a connection to our history—a way of life we all knew growing up here. Everything wasn’t in the grocery store. Our ancestors were able to provide for themselves. Vegetables, meat, eggs—it was done right here on the farm. It’s (farming) a great reward for yourself and other people.”

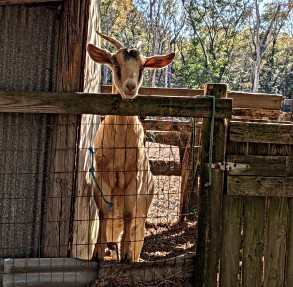

When Small Farm Program Coordinator Berran Rogers contacted him about being part of the farm bus tour, Quinton was surprised. To him, it’s just everyday life. “We’re glad they’re interested in this and want to come down to see this,” he said. “This” is not only scrapple making. In addition to hogs, Quinton raises goats, cows, chickens, and ducks along with hay to feed them and vegetables for family and friends. A couple animals have names, but he only considers one a pet. Cindy, an eight-year-old goat, has that honor as an orphan that he bottle-fed and raised. “She’s like a puppy,” he said. On the other hand, five-year-old, 800-900 pound hog Jack might find himself in the pot one year along with the other farm animals raised for meat, milk and eggs. Another exception is, “I keep certain goats around for the kids at the community church.”

“Farming is an everyday event,” Quinton said. “If you’re going to have animals, there’s no break. They are totally dependent on you. It takes time, effort and resources. I carry that into life’s responsibilities.”

Cindy holds a special place on the Quinton farm

Jack is an impressive hg weighing in at around 850 lbs.

Newell Quinton talks about scrapple making process.

It’s a family affair when it’s time for scrapple making.

Quinton takes conference participants on a tour.

Someone wanted to know what all the commotion was about.

Newell Quinton has come full circle to San Domingo.

Gail Stephens, agricultural communications, University of Maryland Eastern Shore, School of Agricultural and Natural Sciences, UMES Extension, 410-621-3850, gcstephens@umes.edu