The University of Maryland Eastern Shore hosted a discussion on PFAS with representatives from federal and state agencies, researchers and Maine stakeholders April 25. The man-made forever chemicals began getting public attention in 2021 in Maine, which has since become a model for other states as PFAS becomes an emerging concern.

“The focus of this collaborative workshop is a better understanding of PFAS garnered from those who have experienced its challenges and those resolved to finding solutions and ways to move forward,” said Dr. Moses T. Kairo, dean of UMES’ School of Agricultural and Natural Sciences. “Our goal as a university is to identify the research, outreach and support we can provide citizens of Maryland in addressing these issues through our Agricultural Experiment Station, UMES Extension and by exploring the establishment of a dedicated center.”

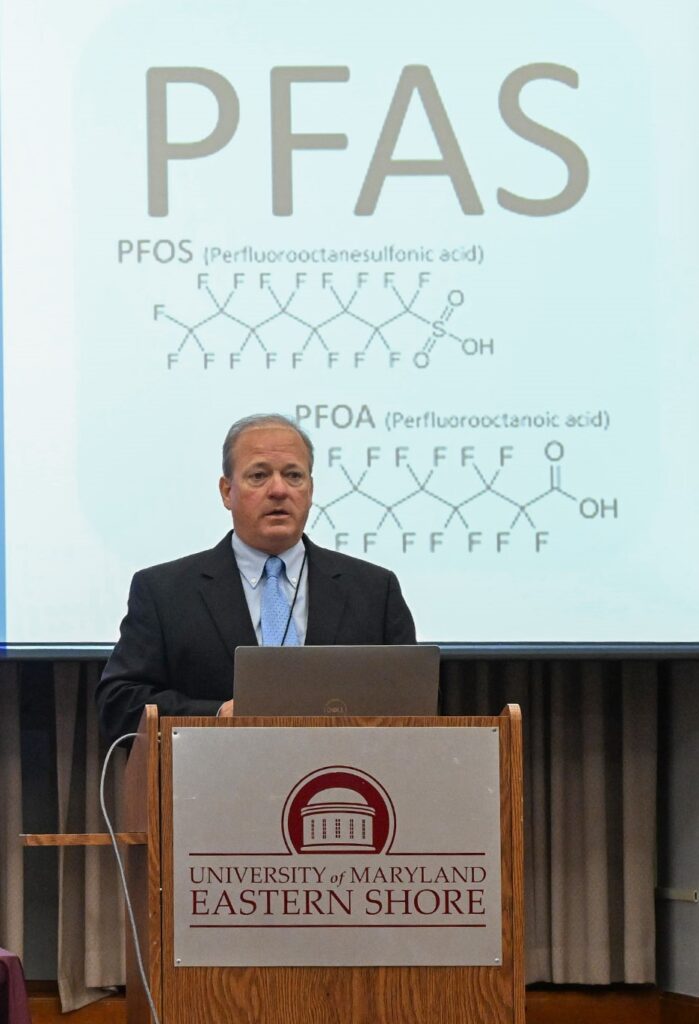

Dr. Greg Allen, (at right) an environmental scientist with the Environmental Protection Agency’s Chesapeake Bay Program Office and UMES alumnus, said the agency is finding that per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances are widely distributed in the environment.

“They have one of the strongest chemical bonds we know of, leading to its persistence and bioaccumulation. This perfect storm will be part of the environmental landscape and for a very long time. It will be in every corner of what EPA does.”

There are an estimated 12,000 compounds in this classification, Allen said. They have been used commercially for water-repellent properties in paper goods, food packaging and clothing, stain resistance, non-stick cookware and firefighting foam among them. The scenario for concern is their leaching into groundwater through effluents and biosolids with the potential to enter agriculture and fisheries.

Allen reported key agency actions based on its four-year (2021-24) strategic plan to address PFAS. On April 10, the agency finalized its maximum contamination limits for six forms of PFAS. The drinking water rule is 4 parts per trillion (for PFOA and PFOS), the limit that could reliably and repeatedly be tested for, he said. The analytical methods have been approved and are pending promulgation. Other areas looking at health effects, air regulation, aquatic life, risk assessments and superfund hazard designation are in progress.

“We want healthy safe farms,” Allen said. “We want to understand the risk and manage it the best we can.”

Congress appropriated $8 million last fiscal year to the EPA to work with USDA to fund research that prioritizes helping farmers, ranchers and rural communities manage PFAS impacts, reduce exposure in the food supply and promote farm viability.

To address PFAS, the U.S. Department of Agriculture through its Food Safety and Inspection Service has collected samples and tested for 16 different PFAS over the past several years (2019), said Gregory Jaffe, senior advisor for regulatory affairs in USDA’s Office of the Secretary. FSIS shares information, including testing methods, with state and federal partners to evaluate local areas of concern and address remediation. Other agencies within USDA also have several PFAS-related programs that can provide support for farmers, rural communities, public water systems as well as programs that invest in PFAS research through its Agricultural Research Service, National Institute of Food and Agriculture, and Natural Resources Conservation Service.

What Maine can teach others on PFAS

This was the case for Maine, where PFAS was first detected in 2016 at a dairy farm. Maine now serves as a model in agriculture for other states through a USDA PFAS Cooperative Agreement. USDA was appropriated (FY23) $5 million for producer support and testing prioritizing states with “established tolerance thresholds for PFAS in agricultural food system or products.”

“Maine met the criteria for an agricultural food product. The rest of us can learn from them,” Jaffe said. “Agriculture, however, is a small part of the larger federal PFAS initiative.”

Maine’s biggest source of contamination originated from industrial biosolids from paper processing plants spread as sludge on agricultural land, a practice banned in 2022, said Dr. Caleb Goossen, Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association’s organic crop specialist. PFAS, he said, enter the farm through water, soil additives and chemical inputs.

A governor’s task force was formed in 2019, with soil and groundwater investigations following two years later. Where there were industrial impacted wastewater, bigger impacts were seen, Goossen said. Also, near an old military base heavily contaminated with firefighting foam.

Maine became the first state in 2021 to ban products containing PFAS, but legislation won’t go into effect until 2030. Last year, a Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry PFAS Response Program created $60 million in funds to help farms that was launched this year. Funds are being used for farmer support and technical assistance, along with an emergency fund for testing support, income replacement and mental health support. A multi-agency collaboration is addressing PFAS issues.

“We’re ahead of the game, but are waiting on federal regulations and guidelines for remediation,” Goossen said. Maine has 68 farms that have at least one test exceeding a screening level.

What’s next for Maryland and PFAS?

“Maryland has taken a proactive role in understanding, reducing and communicating the risk posed by exposure to PFAS as the issue has emerged as a national concern. This includes new sampling and assessment, applying updated science, and working in partnership with other agencies and local governments,” Bradley Baker, a senior program manager with the Maryland Department of the Environment’s Resource Management Program, said after the workshop. “The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s newly adopted hazardous substance rule and enforceable drinking water standards for these chemicals will enhance our work to protect public health.”

Rachel Jones, (at right) director of government relations for the Maryland Department of Agriculture, likewise, supports federal research and science.

“We want to be cautious, data-driven and science-based when we are determining what is safe. Farmers also want healthy soil and the health of the Chesapeake Bay, using best management practices.”

At top:

UMES Extension Associate Dean Dr. E. Nelson Escobar introduces a panel of speakers from Maine sharing their PFAS experience, from left, Dr. Ellen Mallory, professor of sustainable agriculture and extension specialist with the University of Maine; Elizabeth Valentine, a lawyer and director of the Fund to Address PFAS Contamination at the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry; Dr. Caleb Goossen, the organic crop specialist for the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association.

Gail Stephens, agricultural communications, University of Maryland Eastern Shore, School of Agricultural and Natural Sciences, UMES Extension, gcstephens@umes.edu, 410-621-3850.

Photos by Todd Dudek, agricultural communications, University of Maryland Eastern Shore, School of Agricultural and Natural Sciences, UMES Extension, tdudek@umes.edu.