The second 25 years

1911-12 Morgan College catalog

The second 25 years of Princess Anne Academy could easily be called the “Kiah era.”

Thomas Henry Kiah became the school’s fifth principal in 1911 and served in that role until he died in 1936, making him the longest-serving instructional leader in the institution’s first 125 years.

Fifteen years before his arrival, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its landmark Plessy v. Ferguson ruling establishing the “separate but equal” doctrine that shaped America’s attitude about public education for six decades. The Academy would labor under it throughout Kiah’s tenure.

Founded as a church-supported school, the Academy struggled to make do with inconsistent financial support from the Methodist Episcopal denomination. When the second Morrill Act became federal law in 1890 pledging support for public higher education for Blacks, it led the state of Maryland and the church to collaborate in shared oversight of the rural school.

Answering to two authorities with conflicting visions, however, created a dilemma for the Academy in settling on a clearly defined academic mission.

Should the focus be on teaching traditional subjects: math, sciences, social studies, English and classic languages? Or should it train students to be teachers, farmers, mechanics and skilled laborers, such as blacksmiths and wheelwrights?

The few Academy records that survive from that period, and writings by those affiliated with it, suggest the school attempted to deliver both, perhaps spreading itself too thin.

It didn’t help the Academy was on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, regarded for generations by influential leaders in Baltimore and Annapolis, the state capital, as an isolated backwater undeserving of serious attention or support.

Low salaries and no money for new buildings complicated matters for Kiah, who often was rebuffed by the school’s benefactors when he lobbied for additional resources. Between 1899 and 1920, according to Ruth Ellen Wennersten’s 1976 master’s thesis on the evolution of UMES, the Academy received a total of $25,000 in state money, a fraction of what it was entitled to receive under federal guidelines.

Much as it had been when founded in 1886, the Academy of the early 20th century was viewed as a place for Blacks to pursue not much more than a secondary-school education in a nation where segregation was an intractable social contract.

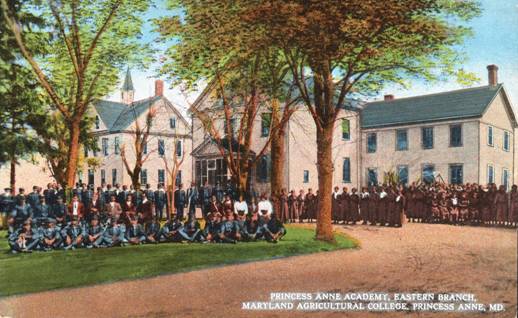

Enrollment during Kiah’s era fluctuated between 120 to as many as 180 students; the faculty typically numbered a dozen – sometimes slightly more. Records from 1913 show the Academy offered summer school instruction for training Black teachers. Eight showed up, and Kiah was one of their instructors.

Tuition was free, but students paid room, board and other fees. They also fulfilled an obligation to help with upkeep around campus and on an adjoining 117-acre farm, where crops and livestock were produced and sold to offset expenses.

When America entered World War I in 1917, the value of land-grant schools – like Princess Anne Academy – took on new meaning. Efficient food production and training in hands-on skills were viewed as crucial to the war effort.

two names in the early 20th century.

Students enrolled at the Academy wore military-inspired uniforms of that period, men paid $10 for theirs and women were charged $5. Diplomas cost $2 at graduation and an athletics’ fee was 50 cents.

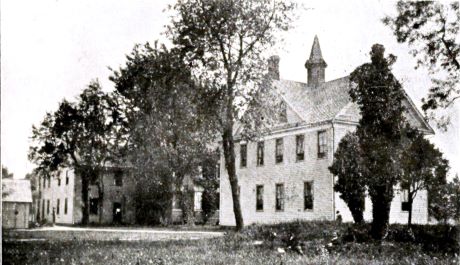

A 1918 fire destroyed the Academy’s administration building and most of its records. Morgan College in Baltimore, which owned the institution in Princess Anne, provided at least $30,000 to rebuild the lost building, but new structures were few and far between in that era.

By the mid-1920s, Kiah envisioned his school embracing a curriculum modeled after those of Tuskegee and Hampton, two respected peer institutions. College-level instruction in agriculture and home economics was introduced. Graduates would have a foundation to finish their studies at other, more comprehensive four-year colleges – typically in another state.

Kiah’s peers disparaged the Academy for its lack of focus. Sketchy record-keeping brought spending priorities into question, and he was not immune to the criticism.

Unable to fully support its branch campus, Morgan College transferred administrative control of Princess Anne Academy to the University of Maryland in 1926. That enabled the state to keep Blacks and whites pursuing higher education segregated at two public land-grant institutions while remaining in compliance with regulations to receive federal aid.

Just before the Great Depression, enrollment at the Academy was a robust 160 students. Four years later, records indicate, the number of students plummeted to fewer than three dozen. It was during this period the Academy began phasing out high school classes and shifted its emphasis to college-level instruction.

By the mid-1930s, the state of Maryland made the first of four $25,000 annual payments to Morgan College to acquire the Academy outright. A year later, official documents referred to the institution as Princess Anne College, a reflection of “increased offerings” in such subjects as agriculture, home economics and mechanical arts.