Students attending Princess Anne Academy in the first decade of the 20th century did not have to look far to see how education could be transformative.

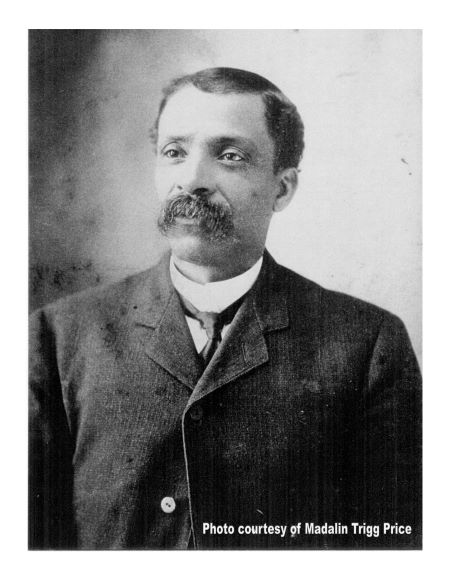

Principal Frank Trigg lost an arm in an accident on a farm where his parents were enslaved.

Unable to do intensive manual labor, Trigg channeled his curiosity and intellect into overcoming his handicap. He went on to become widely recognized as one of his generation’s pioneering Black educators.

Trigg was born in the early 1850s1 to Frank and Sarah Ann Trigg2, servants to Virginia Gov. John B. Floyd. Following the Civil War, he enrolled in Hampton (Va.) Normal and Agriculture Institute, a school for freed Blacks opened to train teachers.

Hampton is where Trigg found his life’s career path — education and agriculture — and crossed paths with Booker T. Washington. Trigg graduated from Hampton with honors in 1873 and taught grade school for two decades, first in Abingdon, Va., and then in Lynchburg, Va., where he was that city’s first Black male teacher and its first Black high school principal. His Lynchburg home at 1422 Pierce St. is a historic landmark.

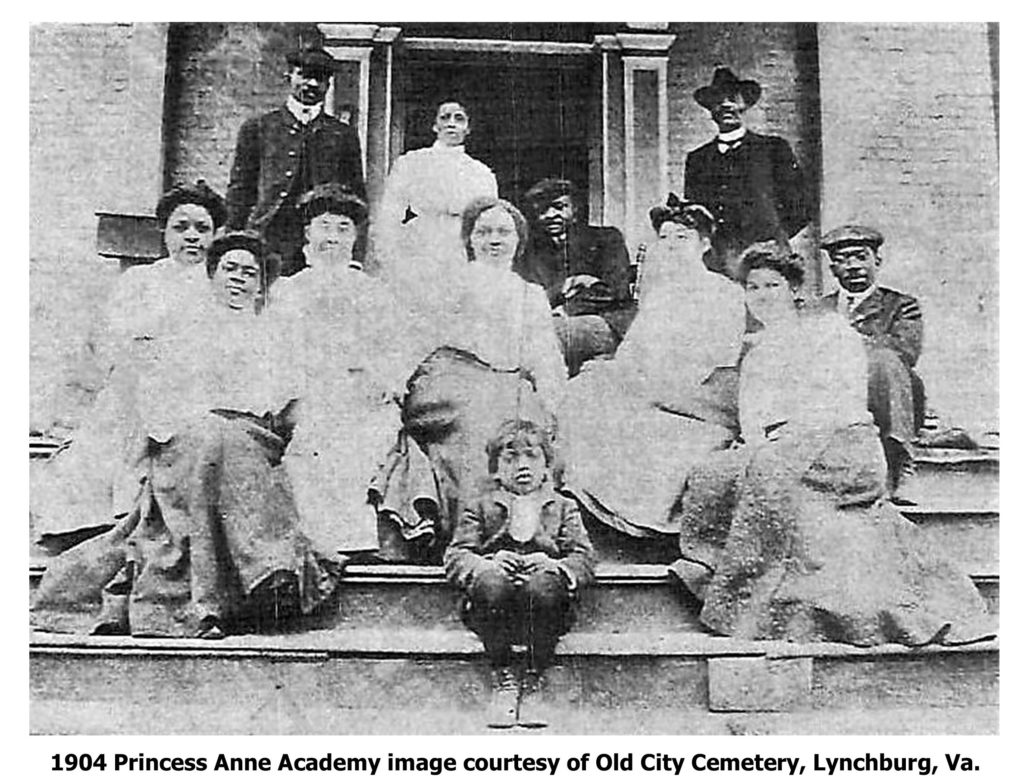

When Pezavia O’Connell left the Princess Anne Academy’s principal post in 1902, the school’s leaders turned to Trigg, a popular and successful secondary school educator in Lynchburg. The academy had 12 faculty members at the time.

Enrollment grew from 50 (the previous academic year) to 133 students by the spring of 1903, and “a large barn, a hennery and piggery” were added to upgrade instruction in agriculture studies.3

The Colored American newspaper published a “Men of the Hour” profile in early 1903 praising Trigg as a forward-thinking educator.

“He will finally win his way to the front of the field of education among his people,” Hampton founder Samuel C. Armstrong is quoted as saying.4

The Somerset Journal, a short-lived local newspaper in Princess Anne, said Trigg “deserves the highest commendation for placing the Princess Anne Academy at once on its feet.”4

Trigg came to the academy during a national movement to develop agricultural instruction at historically Black schools. He saw education being the great economic equalizer for Blacks in a segregated nation, and encouraged students to purchase land and homes.

In addition to science, he taught the Bible, child psychology, hygiene, literature, pedagogy and geography.

Trigg presided over the academy’s first four-year class to graduate with the equivalent of high school credentials in 1904; it consisted of nine students. By 1906, enrollment had grown to 188 students, some of whom pursued training in trades like blacksmithing, carpentry and tailoring.

A man considered ahead of his time, he believed in educating boys and girls and made sure his students – as well as his own children – received the best education available.

One son (Harold L.) served as president of two historical Black colleges, another (Frank R.) was a physician in the Norfolk area, a third (Edward G.) was a veterinarian and their brother (Charles Y.) was a Methodist Episcopal pastor.

The elder Trigg left Princess Anne Academy in 1910 with high praise for a successful tenure, returning to Lynchburg to lead Virginia Collegiate and Industrial Institute, which also was a branch of Baltimore’s Morgan College.

John Oakley Spencer, Morgan’s president, described his colleague as “a teacher of ability, a good disciplinarian, and accomplishes his work with little friction.” 5

In 1915, Trigg became president of Bennett College in Greensboro, N.C., where he spent the next 11 years before retiring. He died April 21, 1933 and is interred in Lynchburg’s historic Old City Cemetery. His wife, Ellen Preston Taylor Trigg, died in 1936.

Trigg Hall, a Colonial Revival building at the eastern end of UMES’ Academic Oval that houses agriculture programs, was named in his honor in 1957. The university posthumously awarded Trigg an honorary doctorate in May 1992.

Footnotes:

1- The 1880 U.S. census listed Trigg’s age as 28 and living with his wife in the same Abington, Va. household as his parents.

2 – Old City Cemetery Museums & Arboretum, Lynchburg, Va.

3 – Southern Workman, Jan. 1903 Vol. 32, No. 5, pg. 253

4 – The Colored American, Feb. 7, 1903, pg. 1

5 – Southern Workman, Feb. 1916, Vol. 46, No. 2, pg. 123