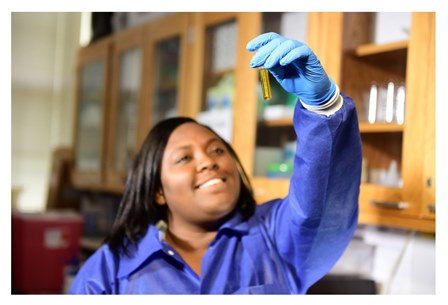

Dr. Tracy Bell is focused on finding new ways to treat diabetes

Thursday, September 13, 2018

Next time you gaze into an aquarium to watch zebrafish zip to and fro, you might just be looking at a 2-inch long vertebrate capable of pointing the way to treating high blood pressure and diabetes.

That’s because the small fish with black and white horizontal stripes share 60-to-70 percent of the same genetic characteristics as humans.

Who knew? Plenty of health researchers, it turns out.

The fish, which resemble minnows, have been helping scientists get a better understanding of the biological processes of muscular dystrophy and cancer.

Now, UMES biology/physiology professor Tracy Bell wants to try her hand at studying zebrafish to see if they might unlock the mysteries of a common blood disorder that affects millions of people.

This past spring, Bell was awarded a $299,996 National Science Foundation grant to support research focusing exclusively on the kidney functions of the prolific tropical fish from Southeast Asia.

In collaboration with UMES colleague Dr. Linda Johnson, she used external funding to build a three-dimensional wall of 10-gallon aquariums in a first-floor lab in George Washington Carver Science Hall that can house upwards of a thousand zebrafish.

In her grant application, Bell described her research project thusly: “The goal … is to investigate the role of insulin in regulating sodium and water transport in the kidney.”

She writes that she hopes to “develop a novel methodology to assess the water and sodium regulation in vertebrates and … advance our knowledge of basic mechanisms of vertebrate kidney transport and fluid balance.’

While her NSF grant supports basic science research, the broader impacts of her project might provide a better understanding of how the kidneys regulate sodium and water balance and in turn maintain good blood pressure. It is well known retention of too much salt (sodium chloride) can contribute to high blood pressure, but the mechanisms have yet to be fully delineated, she said.

Those are the building blocks around which Bell will structure her research.

It turns out the miniscule (and flat) kidneys of a zebrafish share enough of the same “homology” traits as the bean-shaped organs in human. Bell said using zebrafish as a model organism to explore blood pressure regulation “is a new frontier.” During most of her graduate and postdoctoral training, rodents were the organism of choice.

The National Science Foundation program that awarded Bell the grant is designed to support young faculty members just starting their teaching and research careers. Bell joined the UMES faculty in 2014 in her first full-time teaching position.

She is hopeful the NSF grant will enable her to gather enough data to establish a foundation so she can compete successfully for additional external support and continue the research long-term. Most researchers will tell you that discoveries emerge after years of tedious, methodical study and analysis.

Bell has one graduate student and four undergraduate students actively involved in the research project.

“The idea is to get them in the lab and give them the tools to get to the next level” of academic achievement, Bell said.

Sherene Black, the doctoral candidate in toxicology, said working alongside Bell has been an eye-opening experience.

“It’s exciting to know the work we’re doing might someday be able to help people stay healthy,” Black said. “It’s been a blessing to have this opportunity.”

The windows of Bell’s lab are covered so she and her student mentees can control feeding and breeding cycles, aided by a timer that ensures the room is dark a consistent number of hours daily. Of course, water temperature and its chemical composition are closely monitored as well.

And it’s no small task doing necropsies on organisms as small as a Danio rerio, the Latin name for zebrafish.

“It requires a lot of patience and concentration,” Bell said. “Hopefully, by studying the zebrafish as a model, we’ll be able to get a better understanding of vertebrate kidney function.”