1940 alum has fond memories of growing up in Princess Anne

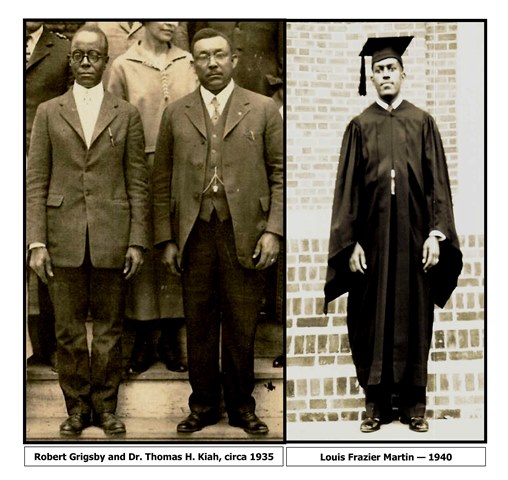

Dr. Thomas H. Kiah, the dapper leader of old Princess Anne College who died in 1936, left a lasting impression on most people he encountered – an observant Louis Frazier Martin among them.

“I really admired him,” recalled Martin, now 101. “He was basically a minister the whole community had a lot of respect for.”

University of Maryland Eastern Shore alumni leaders aren’t certain, but they believe Louis F. Martin might be the institution’s oldest living graduate as the 132nd anniversary of its founding on Sept. 13, 1886 approaches.

He was born July 3, 1917 in Princess Anne, where Louis Henderson Martin, his father, was distinguishing himself as Maryland’s first African American agriculture extension agent. The elder Martin’s office was based at the state’s historically black land-grant campus.

The Martin and Kiah families were large and routinely mingled “like two peas in a pod,” said Martin, a retired agriculture educator.

“I knew them before I went to college,” Martin said.

In order to do his job, Martin’s father had a (circa) 1916 Ford Model T – one of three people and the lone African American in the Princess Anne area that his son recalls driving cars. The others were a doctor and a lawyer.

“It was either that, or (visit farmers) on horseback or (by horse-drawn) buggy,” Martin said with a chuckle.

Louis F. Martin and his twin sister, Lourene, initially enrolled in 1935 at Hampton Institute, their parents’ alma mater. After the first year, Lourene transferred to Mercy Hospital in Philadelphia to study nursing.

As the Great Depression lingered, Martin and his younger brother Walter opted to save the family money and finish their studies back home at Princess Anne College. Louis earned a degree in agriculture education, and was followed by Walter and five other siblings as graduates of the school.

In the spring of 1940, Martin and 10 classmates posed for pictures in their regalia in front of a new gymnasium / auditorium built with Works Progress Administration funds used for brick-and-mortar projects. The building, since demolished, would bear the late Dr. Kiah’s name.

“It was a small group – it was like a family,” he said. “We got along fine, and we didn’t have the problems like you see today. Everybody wanted to graduate. Everybody behaved themselves.”

Martin fondly remembers Robert Grigsby, who was named the college’s leader upon Kiah’s death, as “a very fair gentleman. All your academic problems came through him. The students loved him.”

Martin took a job after graduation teaching agriculture and science at an all-black high school with three faculty members in Howard County (Md.), where he also served as dean of men. War was brewing in Europe, however, and he was drafted in March 1941. He finished the school year before reporting to the Army.

His wartime experiences reflected those of other college-educated black men who encountered skepticism about their leadership skills. Martin persevered, however, and left active duty as a logistics officer who served two years in Britain and had a hand in decommissioning the air field used by the renowned Tuskegee Airmen.

After his discharge in 1946, Martin earned a master’s degree from the University of Illinois and went on to teach agriculture at the college level, first at Florida A&M (1954-1959) and then at Virginia State until he retired in 1982.

While Martin was living in Florida, Life magazine came calling at Happyland, his parents’ homestead near Eden. The weekly periodical’s Sept. 19, 1955 edition featured a lengthy article: “Degrees by the Dozen on $40 a Week,” a tribute to Martin’s parents putting their 12 children through college on an extension agent’s modest salary.

Martin missed the group photo of the family that ran across pages 188 and 189, but the magazine did include a photo of him in his military uniform.

The national attention didn’t have much impact on his life, he said.

“I had already patterned my life in what I was going to do. It didn’t excite me. I have never sought publicity. Being a farm boy, I just live one day at time,” he said.

Martin retired to South Chesterfield in central Virginia, where he lives with his daughter, Sheila Martin Brown, who good-naturedly describes herself as his social secretary and housekeeper.

He still drives and walks regularly for exercise. Brown says her father is a popular speaker and draws energy from discussing his life as a member of the Greatest Generation that spanned much of the 20th century. (Including 22 years as an Army reservist, Martin earned the retired rank of Lt. Col.)

Brown, also retired, followed her parents and all four grandparents in getting a college education.

“I grew up knowing I would be going to college, because that’s what we do in our family,” she said. “The only question is where would I go (Hampton), what would I major in (business).”

Martin attributes his longevity to “eating good food and doing things in moderation.” He calls himself “a staunch (Presbyterian) church member and elder” who looks forward each week to Sunday services.

When making public appearances, he’ll don a tie and suit coat, no doubt influenced by memories of a fellow educator whom he admired growing up.

Dr. Kiah, he said, was “very particular about his dress. He usually wore a suit with a ‘cut-away’ jacket and grey vest.”

The jacket, “had tails that he would sweep back when he sat down,” Martin said. “He also had a pocket watch and used small glasses that were pinched on the bridge of his nose.”

Photos of Kiah in the university’s archives confirm that memory