During the 2011-12 academic year, UMES celebrates a journey from humble beginnings as a secondary school for Negroes in post-Civil War America to a vibrant, culturally diverse university taking on 21st century challenges.

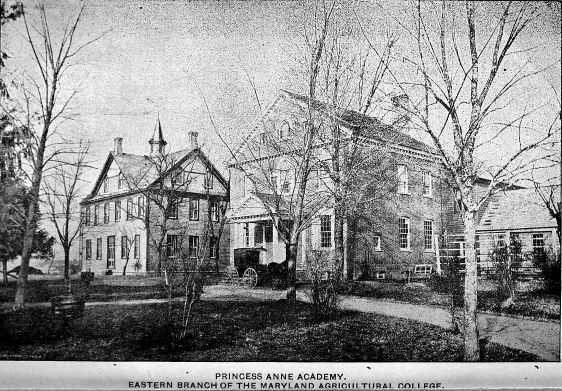

The school opened Sept. 13, 1886 with nine students in a Colonial-era farmhouse on 16 acres, a modest tract that remains the physical and emotional heart of what has grown into a 745-acre campus.

One hundred twenty-five years after its founding, the institution is academic home to some 4,500 students and nearly full-time 200 faculty members on a picturesque campus between two branches that form the Manokin River in Somerset County, Md.

It all began, as many historically black institutions and as the nation itself did, with inspiration from the church.

Leaders of the Methodist Episcopal denomination in Maryland saw a glaring need to provide an education to the children of former slaves and freedmen that would empower them to be productive citizens.

The notion took root initially in Baltimore, where the Centenary Biblical Institute was founded in 1867. Its enrollment grew steadily over the next decade and a half, prompting Centenary’s leaders to establish a satellite campus on Maryland s Eastern Shore.

While much of America turned a blind eye to Jim Crow laws, the Ku Klux Klan and racial prejudices hundreds of years in the making, two men-of-the-cloth – – one black, the other white – – are widely credited in church conference records with founding a co-educational prep school that would evolved into the University of Maryland Eastern Shore.

John A.B. Wilson, a white Methodist Episcopal minister, purchased a 16-acre farm east of Princess Anne for $2,000 in the summer of 1886, according to a property transaction deed on file in the Somerset County courthouse archives.

Committed to treating blacks with dignity, and to his friendship with John R.S. Waters, pastor of what is now Metropolitan United Methodist Church in Princess Anne, Wilson transferred his property to the regional church conference for use as the site for a school. By mid-September 1886, the Delaware Conference Academy opened its doors as the Princess Anne branch of the Centenary Biblical Institute.

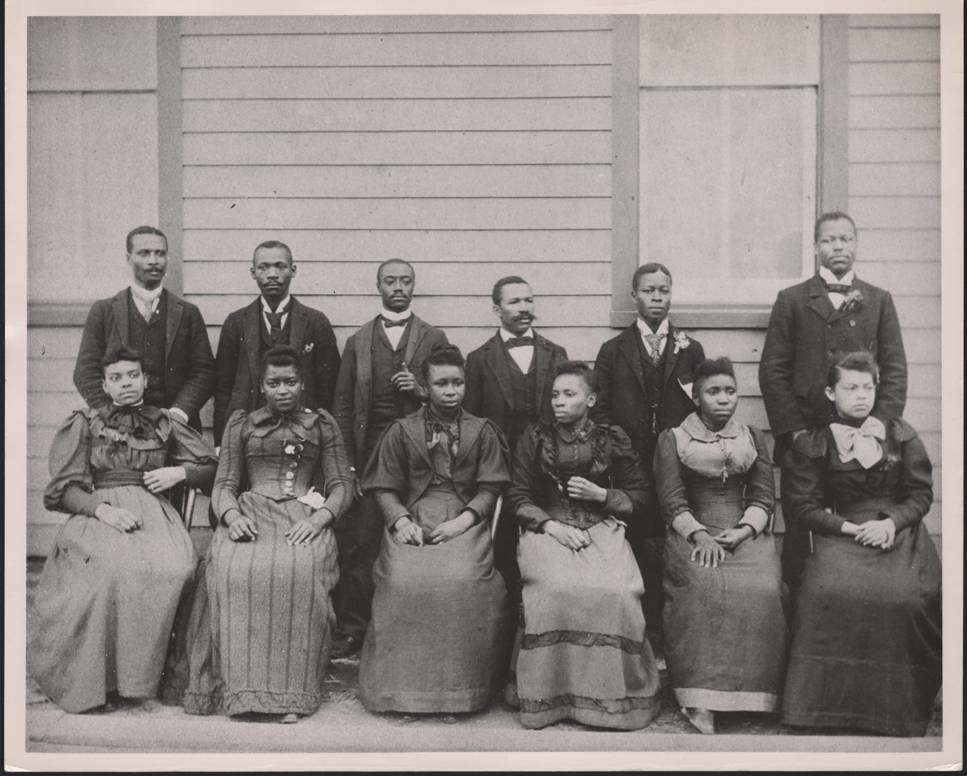

The first instructional leader was Benjamin Oliver Bird, a Centenary graduate. Bird, his wife, Portia, and the Rev. Jacob C. Dunn, shared teaching responsibilities in the early years. By the spring of 1887, the Academy’s enrollment reportedly had grown three-fold to 37 students.

Math, geometry, algebra, physiology, history, geography, grammar and rhetoric were the subjects taught.

Somerset County was mostly untouched by the Industrial Revolution, so the Academy grappled with how it should teach students to run a farm and related skills of the era. Church leaders also saw the Academy as a place that would nurture teachers (women) and ministers (men).

Congress enacted the second Morrill Act Aug. 30, 1890, which committed the federal government to underwriting agriculture, science and engineering instruction at historically Black schools of higher learning.

Throughout much of the 1890s, the school’s annual operating budget hovered around $3,000-to-$4,000, a mixture of federal funds and money from the Methodist Episcopal church, which formed a partnership with the state in sharing oversight of the institution. By the middle of the decade, the school was commonly referred to in annual church conference yearbooks and newspapers of the day as “Princess Anne Academy.”

From the start, the Academy found itself conflicted over its mission. The church emphasized traditional academic and intellectual development, which was in contrast to industrial or vocational training required of schools that took federal aid to fulfill land-grant objectives.

Nevertheless, students found their way to Princess Anne. While graduation rates in the 1890s were low — generally a dozen or fewer per year – – enrollment was typically 100 or more men and women.

Under Bird, the campus footprint grew almost eight-fold to slightly more than 120 acres. When he died April 26, 1897, his wife, Portia E. Lovett Bird, became the Academy’s principal.

Portia Bird held the post for two years before her death on Nov. 25, 1899. The couple is buried on campus not far from where they lived and taught.

Pezavia O’Connell’s brief tenure as principal was a milestone for the Academy. The Ivy League-educated O’Connell was the school’s first leader who held a doctorate degree. A strict Methodist fundamentalist, he continued the curriculum developed under the Birds.

Frank Trigg, a contemporary of Booker T. Washington, became the Academy’s fourth principal in 1902. Educated at Hampton (Va.) Normal and Agriculture Institute, Trigg put his stamp on a curriculum that attempted to balance instruction in the liberal arts and industrial skills of the day.

A year after Trigg arrived, the Academy started a night school, but it proved to be short-lived.

By the middle of Trigg’s tenure, enrollment blossomed to 185. His faculty included instructors educated at Michigan Agriculture College (now Michigan State University), Cornell and his alma mater, Hampton.

Yet the Academy labored under constraints. In the early 20th-century, many young blacks on the Eastern Shore had limited access to a traditional high school education, so the Academy attempted to fill that breach.

The state of Maryland, meanwhile, steered the bulk of federal aid it received for land-grant instruction to its flagship school in College Park — then known as the Maryland Agricultural College, leaving the Academy with a disproportionate fraction of the state’s annual Congressional allocation.

When Trigg stepped down in 1910, he was succeeded by Thomas H. Kiah, who would become a seminal figure at his alma mater for the next quarter century.

Editors’ note: – Beginning with this installment (first published Aug. 29, 2011), this online journey explores the people, places and things that shaped UMES’ colorful, distinctive history.