The foundation for the present-day University of Maryland Eastern Shore was laid during the mid-20th century.

In the midst of the Great Depression, the state agreed to purchase Princess Anne Academy for $100,000 from Morgan College in Baltimore, which had operated it since 1886 as a satellite campus.

The transaction was an important milestone. Although private and church-affiliated, the Academy functioned as a public land-grant institution under the second Morrill Act of 1890, which enabled the state of Maryland to keep its flagship school in College Park segregated while retaining access to federal aid.

A Feb. 5, 1937 article in The Baltimore Sun quoted University of Maryland president Harry C. “Curley” Bird, a Crisfield native, as saying “If we don’t do something in Princess Anne, we’re going to have to accept Negroes at College Park, where our girls are.”

That attitude was prevalent when “separate but equal” shaped America’s public education policy. It would remain that way until the U.S. Supreme Court handed down the landmark 1954 decision, Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas et al.

When Thomas H. Kiah , the long-time principal in Princess Anne, died in Dec. 30, 1936, the school had been trying to move away from its private, secondary school roots in favor of a more rigorous, college-level curriculum. In some publications, it was referred to as Princess Anne Junior College.

Historians and critics differ on the success of those efforts.

The year after Kiah’s death, the course catalog displayed curriculum changes and described the school as “Princess Anne College,” a signal it was becoming an institution of higher learning.

In June 1938, college records show the first class of 17 students completed work on four-year degrees and graduated.

Tuition for in-state students remained free, yet enrollment declined.

Scholars note middle-class Black families viewed Princess Anne College as a good value during tough economic times, but matriculating to the campus on Maryland’s lower Eastern Shore was not easy.

The Chesapeake Bay bridge connecting the Eastern Shore and Anne Arundel County would not open until 1952; a similar span connected the Delmarva Peninsula with Norfolk, Va. opened in 1964.

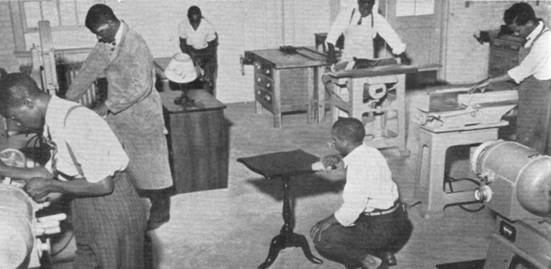

The college struggled with its identity, offering instruction in vocational trades as well as the traditional subjects of arts and sciences.

At least two studies of the state’s public college system questioned the quality and viability of Princess Anne College, a cloud that hung over the school into the late 20th century.

As the nation emerged from the Great Depression, the college’s image also changed. Fire was a constant threat to old wooden structures dating back to the school’s early years, but $210,000* from the federal Works Progress Administration poured in to improve utilities and construct three brick “fireproof” buildings, two of which still stand.

Those investments signaled that despite the criticism about its academic programs and fluctuating enrollment, Princess Anne College was becoming an Eastern Shore fixture.

World War II brought its own stresses and opportunities to the college. Male enrollment understandably declined, and college leaders organized letter-writing campaigns to boost the morale of faculty and students serving in the military.

During the 1943-44 school year, records show, enrollment hovered around 50 students.

The man who guided the college in the post-Kiah era until after World War II was Robert Alexander Grigsby. For reasons that are unclear, Grigsby held the title of “acting dean of administration and registrar” during his 10 years at the helm of the college.

Grigsby presided over an institution that more vigorously embraced the traditional land-grant mission of teaching agriculture, home economics and mechanical arts along with junior college-level instruction in the arts and sciences.

In his 2002 history of UMES, “Polishing the Diamond,” William P. Hytche Sr. concluded “the land-grant mission guaranteed the school’s survival; but oddly enough, while it pleased Whites, rural Blacks felt humiliated by the thought of being trained do what slavery had … forced them to do.”

When Grigsby retired in 1947, the University of Maryland’s governing board turned to John Taylor Williams, a Louisiana native who ushered in a dramatic new period in Princess Anne. The governing board named Williams “president,” signaling a growing stature for the institution. The institution’s identity also changed; by the 1948-49 school year, it was known as Maryland State College – “a fitting symbol for its new life,” the course catalog declared.

poultry science educator

Williams’ impact on the college was immediate and long-lasting. Drawing on his experience working at other colleges, he set about reorganizing the academic programs into four formally recognized disciplines: agriculture, home economics, mechanical arts and arts and sciences.

Enrollment during Williams’ first year (1947-48) was 163 students, who were taught by 11 faculty members. The following academic year, enrollment doubled and the number of faculty tripled. One account described on-campus housing as having four-to-six students assigned to rooms designed for two.

Despite criticism in the press and the social pressures associated with a segregated education system, Williams aggressively pushed Maryland State into becoming full-fledged institution of higher learning.

In addition to a more-grounded curriculum, the college embraced extra-curricular and co-curricular activities, such as fielding highly competitive sports teams, sponsoring a Reserve Officer Training Corps unit and crowning an annual campus “queen.”

By the 1950s, Maryland State was recognized as a “Division of the University of Maryland in Princess Anne” – not merely a distant branch campus. When the turbulent 1960s dawned and the Berlin Wall went up in 1961, the Williams era was in full swing.

(*) April 20, 1940 edition, The Baltimore Sun, pg. 4