All over the country, buildings have been burned and dynamited. The business of the colleges has been disrupted and ignored. Rights, other than the claimed rights of students, have been repeatedly violated. The (public’s) anger … and chicanery of political leaders have grown. The end of the academic year found the nation’s universities … battered and beset.”

—John T. Williams, July 30, 1970

Those remarks, made in the closing days of John Taylor Williams’ 23 years as the only president of Maryland State College, were a big-picture assessment of the turmoil America faced as the turbulent 1960s ended.

Like many colleges during that time, Maryland State was not immune to civil disobedience and Williams was the focus, or at least seen as an impediment, to change students were demanding.

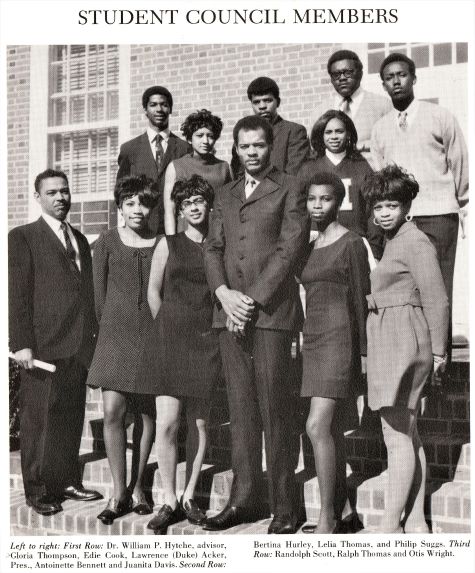

Lawrence “Duke” Acker (’70) led students in a series of demonstrations protesting conditions at the institution. While mostly peaceful, the protests were strategic and well-planned. To aid their cause of securing additional resources and a better campus environment, Acker, the Student Government Association president, and his “lieutenants” cultivated support from the students, their parents and Black residents of Princess Anne.

Having watched previous SGA leaders frustrated in seeking redress from the administration, Maryland State students traveled to Baltimore, Philadelphia and Annapolis to meet with parents and political leaders to express their displeasure and demand their college be treated with respect.

Throughout the 1969-70 school year, the students repeatedly demanded Williams’ resignation. In the spring of that year, they staged a sit-in and filled the halls of the administration building only to be denied an audience with Williams. Unflappable, the students took their protest to the president’s home that same night and eventually took over the administration building, which now bears Williams’ name.

Joanne Johnson-Shaw (’72), a sophomore at the time, recalled that as tensions increased that night, the state police and the Army National Guard were called in. Using helicopters and armed guards, some 180 students, including Johnson-Shaw and Acker, were taken into custody and transported to two locations – the Princess Anne police station and the National Guard Armory in Salisbury.

While students were detained at the Armory, some UMES administrators brought food and some even paid the fines to gain their release from custody. Like their contemporaries during that era, the UMES students were found guilty of disorderly conduct and disturbing the peace, but wore their involvement in demonstrations as a badge of honor, believing their efforts had ignited change.

By late spring, Williams, then 65, decided to retire. Some of the reasons he cited included “the unbearable condition created in the office of the governor (Marvin Mandel) of the state of Maryland,” “a board of regents, which has been unresponsive,” and “the extensive campus unrest.”

Indeed, newspaper clippings show that Williams had no problem with publicly challenging state leaders.

In a May 27, 1970 article about his retirement announcement, The Baltimore Sun quoted from a letter Williams sent to Maryland Secretary of State Blair Lee 3rd, with whom he had clashed: “Your utterances in connection with the present and future status of the chief administrator of the college constitute a dangerous precedent in higher education.”

In an ironic twist, Williams called Acker to his office, where the two adversaries agreed the SGA president would deliver an address at the May 31st spring commencement and say students’ primary concerns rested not with Williams, but with the Board of Regents. The day’s program, however, does not formally list Acker as a speaker at the event where state Sen. Sen. Verda Freeman Welcome delivered the commencement address.

As the summer of 1970 drew to a close, so did the era of John T. Williams and Maryland State College, paving the way for what would become the University of Maryland Eastern Shore, a fully integrated part of the University of Maryland system.