by Bernard C. Steiner, pg. 206

Four dozen buildings where students learn and live and where faculty teach and conduct research were scattered across 745 acres at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore on the 125th anniversary of its founding in 1886.

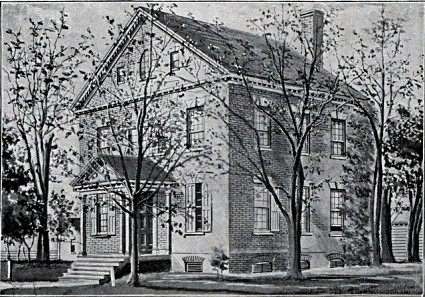

When its first educator-administrator, Benjamin O. Bird , and his wife, Portia Lovett Bird, arrived in Princess Anne in late August 1886 to take charge of the school, they found an elegant but neglected brick mansion on 16 acres of ordinary farm land. Ancillary buildings useful for running a plantation were present as well when the school opened, but the structure known as “Olney” became the foundation of the first institution of higher learning for blacks on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.

Built in 1798 by Ezekiel Haynie, a physician and surgeon in the Continental Army, Olney was constructed in the Federal style popular during the period. It featured Flemish bond brickwork and jack arches with projecting keystones above its windows. The most impressive features were on the façade facing south, a Palladian window on the second story and an oval window — or oculus — above it in the pediment.

Heat would have been provided by fireplaces connected to two chimneys on the house’s north side. No interior images or floor plan are known to exist, but it can be determined from exterior drawings that Olney was built on a center hall plan, allowing for four rooms on the first and second floors as well as a large attic.

Haynie did not have long to enjoy what was one of Somerset County’s finest homes.

Upon his death in 1799, the house passed through the hands of his heirs and other leading citizens of the county, who sold off chunks of the original property so that when physician Aaron Woodruff purchased it in 1870, 16 acres remained. Woodruff died in the early 1880s, leaving the house vacant while an executor of his estate attempted to find a buyer.

History often is made through a combination of initiative, opportunity and coincidence. Such is the case that led Olney to become, as one Methodist Episcopal church leader wrote, the “Athens” of black education on the Eastern Shore.

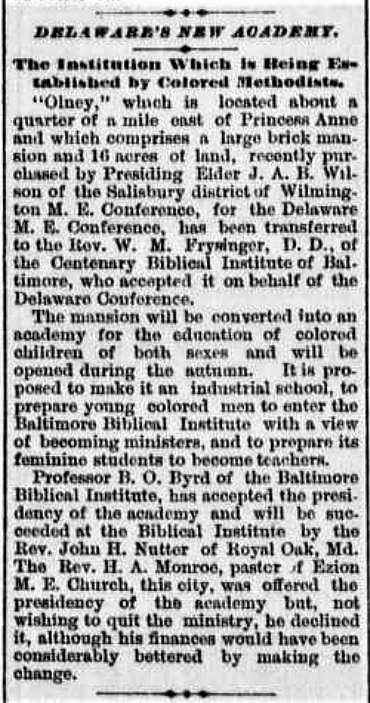

Shortly after leaders of the Delaware Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church and Centenary Biblical Institute in Baltimore concluded that eastern Maryland needed a school for blacks, a search began for a suitable site.

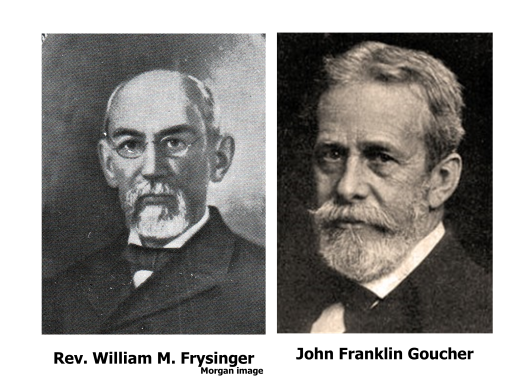

The job fell to the Rev. William Maslin Frysinger, Centenary’s second president, and the Rev. John Franklin Goucher, one of the institute’s board members and a widely respected philanthropist. Their visit to the Eastern Shore, recorded in church documents, was characterized as “a tiresome journey, attended by nothing but unsatisfactory results.” The two men “adjudged the prospect hopeless, and were returning disappointed” when they stopped to stay the night with the Rev. John A.B. Wilson in Princess Anne.

While discussing the tribulations of finding a suitable location, Wilson’s wife, Mary, joined the conversation in “a very unbusinesslike manner.” It was Mary who suggested Olney, which had been offered to the Wilsons by the executor for $2,000. Intensely interested, Frysinger and Goucher immediately set out at 1 a.m. to view the property “from garret to cellar” as “Nehemiah viewed the walls of Jerusalem by night.”

Convinced it could make a fine school, Frysinger and Goucher dispatched Wilson to inquire whether the deal offered to him could be renewed “for a church purpose.” Anxious to rid himself of the last piece of the Woodruff estate, the executor agreed. With a $500 down payment donated by Goucher, who later led a private women’s college in Baltimore that bears his name, Wilson purchased Olney on June 12. He in turn deeded the property to Centenary on Aug. 24, establishing the footprint that became UMES on the outskirts of late 19th century Princess Anne.

Upon their arrival, the Birds must have had misgivings about the prospects of their new station. With determination, however, they persevered. Starting with “nothing but briers and bushes, an ‘old, forsaken mansion,’ which had been used as a granary, with his own hands (Bird) cleared the land, renovated the house; at first one room for a lodging place for his wife and children.”

& State Journal

By Sept. 13, 1886, Bird had renovated Olney to a condition where he accepted nine students into the academy. At year’s end, 37 were in attendance.

Over the years, Olney was modified and rebuilt. A wood frame wing, housing the dining hall on the first floor and the boys’ dormitory on the second, was completed in the first year. Sometime before 1910, another frame addition, which included a laundry and more rooms for students, was added.

In the early morning hours of April 19, 1919, Olney and its additions were consumed by fire, which was thought to have started by an overheated stove in the laundry area. The frame additions were destroyed and only a brick shell remained of the mansion.

A plan was quickly initiated to replace the lost structures. Olney was re-built “on present lines” along with a separate two-story brick building to house a new dining hall and laundry.

During its 86 years of service to the school, Olney was the principal’s residence, a dormitory, faculty housing, a classroom building, a laundry, a dining hall, a practice house for home economics and an administration building. By the late 1960s, Olney, then known as “the Manse,” was deemed too costly to renovate and was razed.

Olney’s spirit, however, lives on in the Colonial Revival architecture of buildings that ring the Academic Oval. If Principal Bird could somehow gaze out a window of J.T. Williams Hall, the administration building, and look to the east where Olney once stood, he would surely be amazed at how the grounds of the “old forsaken mansion” had become an institution of higher learning.