The University of Maryland Eastern Shore’s first 75 years were a period of perpetual uncertainty balanced by unwavering perseverance. The next 25 years were no different.

As the 1960s dawned, the institution took on a higher profile as public four-year college under a strong-willed leader, John Taylor Williams.

Just as American life confronted — and was altered by the upheaval in the ‘60s, the decade dramatically affected Maryland State College as well.

Williams reorganized academic programs so instruction more closely conformed to the 19th-century definition of a land-grant college, yet did not abandon training educators.

Maryland State embraced a reputation of reaching out to students who otherwise might not continue their education beyond high school. That “hand up” philosophy, along with inconsistent government financial support, fueled public criticism of the college’s viability and suggestions of merging Maryland State with the public college in Salisbury 11 miles to the north.

Meanwhile, Williams understood the value of intercollegiate athletics and how successful teams could create an identity for an institution. The 1960s could be described as Maryland State’s golden era in sports.

The football team was a juggernaut, producing an impressive roster of players who went on to the professional ranks. Other sports were equally competitive in a world where segregation on the field and in the classroom lingered after the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court ruling ending “separate but equal” public education.

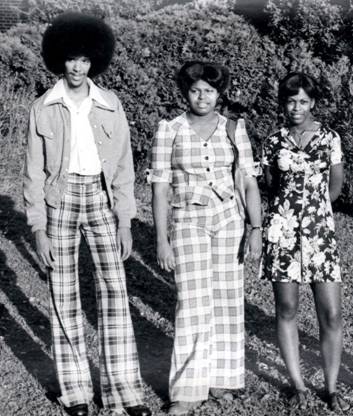

Meanwhile, the civil rights movement empowered Blacks and the downtrodden to stand up for equality. Maryland State students played a role in that movement. They protested about things they didn’t like about campus life; food, housing and outdated classroom buildings. They also saw vestiges of Jim Crow in the surrounding community, and showed their displeasure with acts of civil disobedience.

“We endured. We blossomed. We loved … in spite of the times,” alumna Starletta DuPois (’68) said.

Much as it had in the early years, the college found itself justifying its existence throughout the 1960s and 1970s. There were calls for turning the college’s property into a prison, converting it into a poultry research facility, scaling back the curriculum to make it a community college and placing the campus under the jurisdiction of the University of Maryland in College Park.

The latter was given serious consideration because the federal government was pressing the state to be more aggressive in desegregating its flagship university.

Founded as a private, historically black institution, Maryland State was surprisingly diverse; yearbooks of the era show. In 1969, 127 of the college’s 727 students were white; 25 of the 64 faculty members also were white.

Nevertheless, Williams, a strict disciplinarian, found himself in a maelstrom buffeted by rebellious students and a state-level power structure perceived as giving lip service to its claim of supporting the college. Those dynamics eventually ended his career as a college administrator, yet he held a special place in the hearts of alumni whose lives he shaped.

As Williams exited in the summer of 1970, so too did the name of the institution over which he presided for 23 years.

That new name was the University of Maryland Eastern Shore. It supposedly reflected a new era for the institution, but in reality little changed.

.jpg)

Howard Emery Wright took over from Williams and was interim leader until replaced by Archie L. Buffkins in 1971.

During Buffkins’ and Wright’s combined tenure, a new library named for abolitionist Frederick Douglass and a performing arts center named for entertainer Ella Fitzgerald changed the face of the campus.

While new buildings were welcomed – and celebrated – outsiders continued to scrutinize the university’s quality. Two reports in the mid-1970s questioned the university’s effectiveness and usefulness.

Then along came William P. Hytche , whom Williams hired as a math professor in 1960 and who steadily climbed the leadership ladder. He was named the university’s chief executive in 1975 and quickly became a unifying figure.

When yet another panel — this one headed by respected Salisbury attorney John W. T. Webb — again put the university under the microscope, it was Hytche who emphatically and eloquently defended it.

“Rumors of merger, of change in governance and closing the University of Maryland Eastern Shore have kept this campus off balance,” Hytche wrote in “Polishing the Diamond, A History of the University of Maryland.”

Hytche ushered in a new academic era at UMES, winning support for eight new undergraduate degree programs, a stand-alone graduate program and a joint graduate program. Construction management technology, hotel restaurant management, environmental science, engineering technology and physical therapy are among the university’s signature programs.

His son, William Jr., said the elder Hytche believed that “when a student came to campus, everyone was expected to toe the line. But it was also a place where you knew you would be mentored, and watched over – where people cared.”

Bill Jones (’78), the son of two long-time university employees, said “there was a real sense of community here.”

“Everything we did was circumscribed by race,” Jones said. “We were all very aware we didn’t have what others had, but much was expected of us nonetheless.”

Hytche pursued establishing international partnership with vigor. Jones said the UMES campus of the 1970s attracted its share of international students, an opportunity that exposed students like him to other cultures.

Hytche found an ally in John S. Toll. As president of the University of Maryland starting in 1978, Toll championed UMES’ cause for fair treatment by the new governance system under which both campuses operated. Toll made available faculty members from College Park to UMES, even arranging for them to fly to Princess Anne.

As the 1980s began, Hytche made the difficult decision to end the football program, which was hemorrhaging financially for years and had the athletics program deeply in debt.

While adding new undergraduate programs were important to stabilizing the university, Hytche also saw the value of its heritage by fostering agriculture instruction and research. To lead that effort, he hired a Tuskegee-trained educator, Mortimer H. Neufville, who a generation later would lead the institution.