Clarence Clemons

Baby boomers who grew up listening to rock ‘n’ roll music knew him by his nickname, the “Big Man.”

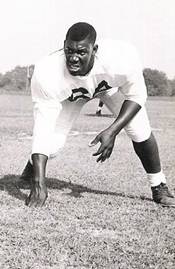

Before becoming a cornerstone of Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band, however, Clarence Clemons was a pretty fair athlete.

Like many Black adolescent athletes of his generation who grew up in the segregated south and matriculated to Maryland State in the 1950s and 1960s, Clemons came to Princess Anne to play football for a Black college powerhouse.

Teammates insisted Clemons had pro-caliber ability. He was set to try out as a lineman for the (Jim Brown-era) Cleveland Browns of the mid-1960s when he suffered a severe injury in a one-car accident, ending any chance of earning a living in the National Football League.

Instead, a talent for playing saxophone that he had been honing since childhood while growing up in Virginia’s Tidewater area eventually made Clemons a lucrative living – and a pop music icon.

The story of how he met Springsteen while playing Jersey Shore bars was chronicled in great detail by popular culture writers enthralled by an on-stage chemistry between an imposing, muscular black man who could wail on a sax with the energy of a diesel locomotive — and a slightly built white singer-guitarist.

Clemons’ life and experiences as an undergraduate, however, went somehow unnoticed – or under-appreciated. Perhaps it was the era and the generation in which he came of age.

It was not until he his death on June 18, 2011 at age 69 that the larger world discovered Clemons’ athletic prowess, something his Maryland State peers quietly had known about for nearly half a century. National media outlets demonstrated a curious fascination with the fact the famed musician also played high-caliber football when the collegiate game was still segregated.

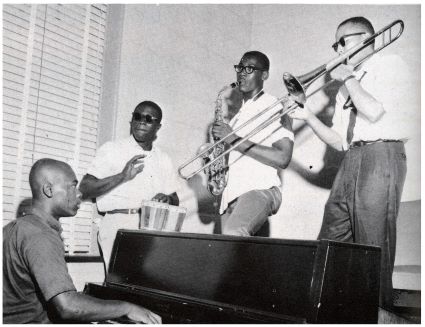

senior Godfrey Mills (trombone)

In the days following his death, classmates and teammates volunteered tributes and colorful anecdotes – reinforced in part by black-and-white images from 1960s-era Hawk yearbooks – of him playing football and the saxophone.

Emerson Boozer, who played professionally with the New York Jets, recalled living in a dormitory athletes shared and hearing dulcet tones wafting from Clemons’ room.

“You couldn’t sleep at night if you were on the same floor with him,” Boozer said. “He’d be blowing that sax. He was musically inclined then.”

Boozer and fellow alumni also remembered the hip music education major – often sporting sunglasses – played in combos alongside fellow student-musicians on campus as well as in local clubs.

Thirteen months before he died, Clemons returned to Princess Anne to receive an honorary degree during spring commencement exercises. On a social network site just moments before the ceremony, he described the honor as “a very special moment in my life.”