Two days before the University of Maryland Eastern Shore was to celebrate the 115th anniversary of its founding, the nation — and the world — came to a standstill.

Terrorism on American soil snuffed out a long-anticipated celebration for the university – a dedication ceremony for an important public works project that changed the face of campus in the early 21st century.

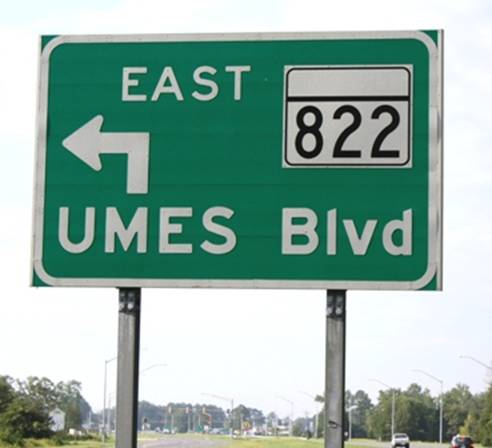

UMES Boulevard – also known as Maryland Rt. 822 – was to be christened by state and local dignitaries the morning of Sept. 11, 2001.

Understandably, the event did not take place. It was never rescheduled.

“People just started using it,” said Dr. Ronnie Holden, then UMES’ vice president for administrative affairs.

Just as “9-11” changed America, the new road transformed the university by connecting the campus directly to U.S. Rt. 13. The new UMES Boulevard also represented a key component in the reconfiguration of campus that included construction of the Student Services Center.

Holden, who joined UMES’ staff in 1977, remembered coming to work earlier than usual that day.

“I wanted to make sure we had everything in place,” he said. “The governor and a lot of dignitaries were coming.”

Donnie Drewer, the lower Eastern Shore’s long-time State Highway Administration engineer, recalled the event was to be “a great hoopla to celebrate the opening of UMES Boulevard.”

For Drewer and late UMES President William P. Hytche Sr., it represented a joint achievement after two decades of lobbying for the road project.

Both pledged they would not retire until the road was built. Hytche, however, retired in 1997 but remained visible in the community. Drewer worked for the SHA for five decades before retiring (in 2016).

“I’m glad Dr. Hytche was able to see the road open,” Drewer said. “I’m just sorry it took so long. I think it has made a huge difference for UMES.”

Holden concurred.

“There’s no doubt it has been important to the university,” Holden said. “It’s a lot easier now to get here; you don’t have to go through town.”

Brian Shane, a (Salisbury) Daily Times reporter, visited UMES that morning to interview Dr. Jackie Thomas, who was serving as interim president after Dr. Dolores Spikes resigned.

While touring the campus, Thomas’ “cell phone was ringing a lot, but he seemed to ignore (them),” Shane said.

Holden speculated some of those calls probably came from him – after a colleague urged him to turn on a television set in his office.

“At some point,” Shane said, Thomas “did pick up the phone, and a confused look came over his face. ‘What? They bombed the Pentagon,’ (Thomas) said to the person on the other end. Nobody really had a clear idea of what was happening.”

Drewer and his colleagues also were unaware of what was taking place in New York, Washington and western Pennsylvania. They showed up at a makeshift stage set up for the mid-morning ceremony.

“We were told there was a national emergency and the governor (Parris Glendening) would not be coming (to Princess Anne),” Drewer said. “We all got in a circle and said a prayer.”

Drewer remembered those who had gathered at the dedication site went to a building on campus and ate the early lunch planned for the Governor.

Shane, the journalist, said, “I don’t recall anyone on campus really showing any awareness or panic of what was happening.” He was summoned back to the newsroom.

UMES administrators decided to maintain a routine schedule for the remainder of the day as most schools did.

“We see how it’s changed America,” Holden said. “At one point, we thought we were invincible.”