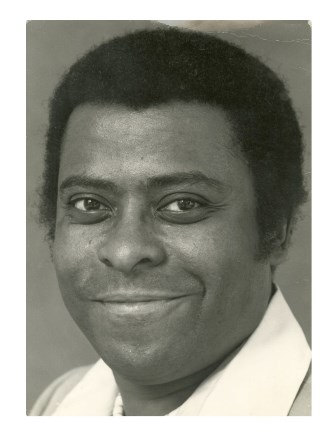

Late illustrator Billy Graham’s early works debut at UMES

Thursday, September 20, 2018

Over a 25-week period earlier this year, the blockbuster “Black Panther” took in $700 million in gross ticket sales domestically, the top-earning movie for the first nine months of 2018.

The name of the late artist, whose creativity in the 1970s inspired the imagery of the film’s title character, was nowhere to be found in the film’s credits.

The University of Maryland Eastern Shore is poised to correct that oversight.

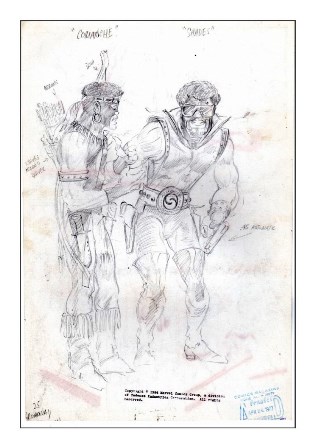

A never-before-seen collection of the early works of Billy Graham – known in the art world as “the Irreverent One” – debuts (Thursday) Sept. 27 at UMES’ Mosely Gallery. A celebratory opening reception is scheduled from 4 p.m. to 6 p.m.

Gallery director Susan Holt heard about the existence of Graham’s early illustrations through a March 8 article in The New York Times chronicling his family’s disappointment that millions of movie-goers don’t know the story of the pioneer behind the featured character in the film.

Near the end of his life, Graham asked his family to preserve a trunk with his sketches and art work from his early days as an illustrator. The collection was known as the “Treasure Chest,” according to the Times’ article.

For more than two decades, Graham’s family was the unassuming custodian of art that few others knew existed. Then, along came the 2018 film that cast a new light on showcasing people of color in science fiction stories.

The backstory portrayed in the Times’ article intrigued Holt, so she reached out to Graham’s family with an offer: the gallery she directs at a historically black institution (where students are taught sequential arts – how to draw illustrations like those in comic books) would welcome the opportunity to display the late illustrator’s works.

Shawnna Graham said “we decided to allow a gallery to display some of my grandfather’s work to bring awareness to … his talents and his importance to the African American culture and history.”

As far as Holt can tell, “this is the first exhibition of these original works.”

The exhibition, Holt said, will showcase some 20 original illustrations in pencil, ink and color, as well as some of the artist’s personal artifacts. The works are on loan from the family, Graham’s estate as well as from private collectors.

“We are very honored for the opportunity,” Shawnna Graham said. “We hope … it will allow the students, faculty and guests to be knowledgeable of what seems to be masked history of African American art.”

Graham is widely recognized as the first black artist at Marvel Comics, where in the 1970s he also had a hand in illustrating Spiderman, The Hulk, Luke Cage, Hero for Hire and eventually breathed new life into an old Stan Lee-Jack Kirby character, the Black Panther, which made his first appearance in 1966 in the “Fantastic Four” episode No. 52.

Brad Hudson, who teaches sequential arts at UMES, said “Graham’s work on Luke Cage and Black Panther lent a degree of authenticity to characters that were primarily treated by white writers and artists.”

“His compositions and page layouts are dynamic and exciting. They break away from the standard grid, panel layout,” Hudson said. “Graham’s story is unique in that he was an African American artist doing canonical work on one of the first African American comic book characters.”

Industry peers recognized Graham’s talents; he became the first black art director and then a managing editor in the comics industry.

Drawing wasn’t his only creative outlet. He won awards for his set designs for stage productions on- and off-Broadway as well as for screenplays. He also acted on television, in film and on stage.

“This first exhibition of his art work at UMES aims to give long overdue recognition to his talent,” Holt said. The university also is taking the extra step of creating a printed catalog of the works on exhibit at the Mosely Gallery.

Graham, who died in 1997, embraced the nickname “the Irreverent One” to differentiate himself from the 20th century evangelist of the same name. Holt has incorporated that moniker into the exhibit’s title.

“Making these works available for public viewing I hope will ultimately start the process of drawing attention to my grandfather’s talents of published and unpublished art,” Shawnna Graham said. “I feel he has not been properly credited or recognized for his talents or the opportunities he assisted with paving the way for African American artists.”