Maryland State College educator revered as a pioneer in African American ballet community

Monday, July 29, 2019

“For the culture” isn’t just a trendy 21st century phrase.

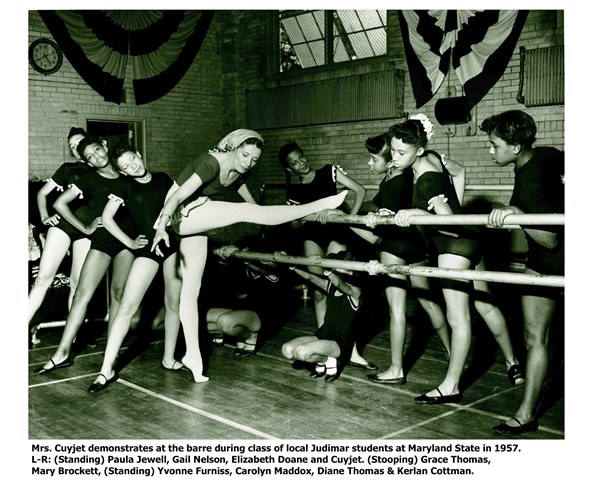

In post-World War II America, Marion D. Cuyjet of Philadelphia played an influential role in diversifying the classical ballet community; she saw a star student, Judith Jamison, go on to perform with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and made time to share her creative gifts with college students she taught in Princess Anne.

Cuyjet (SOO-jay) operated with that same mindset as she provided access for children of color to the art of ballet in Philadelphia from the 1940s to 1970s. She is revered for her determined pursuit of cultural enrichment and opportunity through dance, which she made possible for her students of the Judimar School of Dance she founded in 1948.

She also demonstrated her commitment to equality in the arts during 14 years as an adjunct instructor at what was then known as Maryland State College beginning in 1957.

Born Marion Helene Durham on July 29, 1920 in south Philadelphia, she was the youngest of Alonzo and Frances Durham’s three children. Her parents left Cheswold, Del. for Philadelphia in pursuit of a better life for their family.

As a mixed race descendent from the community of Delaware Moors (West African, Spanish as well as Lenape and Nanticoke Native American ancestry), Cuyjet’s fair complexion motivated her to seek equal opportunity and tear down color barriers for African Americans in the classical ballet community.

In a 1953 Pittsburgh Courier profile on Cuyjet’s impact within the ballet community, journalist Jack Saunders wrote: “Marion is recognized as one of the outstanding ballerinas of the United States, irrespective of race, color or creed.” Saunder’s article describes Cuyjet as “beautiful, statuesque and golden-haired.”

“She was a grande dame of her time,” said Gail Nelson-Holgate, a former Princess Anne dance student and professional performer.

Nelson-Holgate, the daughter of Maryland State’s campus chaplain, was among local children also afforded the opportunity to study under Cuyjet. “She had stories to tell, I’m sure, because of the shade that she was at the time she grew up becoming a dancer herself,” Nelson-Holgate said.

According to “Marion Cuyjet and her Judimar School of Dance” by Dr. Melanye White Dixon, one of those stories happened in the 1930s when Cuyjet’s mentor arranged for her to receive private lessons from Thomas Cannon and study with the Littlefield Ballet Company and school, which later became the Pennsylvania Ballet.

Prior to the civil rights movement, ballet classes were not open to African Americans in Philadelphia. As part of an ensemble, Cuyjet participated in two performances on Wednesday and Friday nights. She performed under another name, but was discovered by some Sunday school friends from the First African Baptist Church Cuyjet attended.

After a performance, the girls went backstage looking for Cuyjet, which revealed to the school’s directors they had unwittingly mistaken her for being white. Cannon told her not to come back. Cuyjet’s mentor, Essie Marie Dorsey, instead arranged for Cannon to teach her privately.

* * *

Cuyjet began formal dance training at age 14 under Dorsey’s tutelage and would later go on to partner with Sidney King and open the Sidney-Marion School of Dance before parting ways as business partners in the late 1940s.

She initially began teaching ballet in her home in 1945 to provide therapy for her daughter Judith, who had rheumatic fever. She later founded the Judimar School of Dance at 1310 Walnut St., Philadelphia’s Center City district.

“She named it Judimar,” said Cuyjet’s daughter, a 1961 Maryland State alumna and retired educator. “My mother named the studio after me. Judith and Marion. I was included.”

Cuyjet moved her studio three times to different locations on Walnut Street due to racism. “Some business owners in the building didn’t like the fact that beautiful brown-skinned children were coming through their neighborhood, even though we were well-behaved,” Judith said.

Cuyjet was unfailingly generous, according to Joan Myers Brown, founder of The Philadelphia Dance Company (Philadanco). “Mrs. Cuyjet took her students to study in New York in the summer. When I decided I wanted to open my own school, I questioned her about how to run a dance school. She even came to teach some classes for me when I opened my school,” Myers Brown said.

Cuyjet staged many successful ballets, ranging from performances for the Philadelphia Cotillion Society-Heritage House to musicals and ballets at Maryland State featuring college students and Judimar students.

She organized a campus performance annually at Maryland State. The 1968 production of “Go Now, Pay Later” toured the state of Maryland. Her Maryland State productions included “Caribbean Capers (1957), “Carmen Co-ed” (Bizet) (1958), and “Amahl and the Night Visitors” (Menotti) (two annual performances 1960-1961).

* * *

Cuyjet’s commitment to diversity and opportunity in the world of ballet is evident as a result of the impact of her Judimar school. Among her students who went on to professional acclaim include Delores Browne Abelson (New York Negro Ballet), China White (first dancer of color to receive a scholarship to the Pennsylvania Ballet Company), Lee Parham, Johnny Hines and Judith Jamison (Artistic Director Emerita, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater).

Dr. Melanye White Dixon, a retired associate professor emeritus of Ohio State University’s Department of Dance, interviewed Cuyjet from 1982 to 1989. In White’s doctoral dissertation, Cuyjet spoke fondly of her time in Princess Anne.

“I took my little company to perform and I never left,” Cuyjet said. “I stayed 14 years. The president of the college (John T. Williams) was very enamored with this ballet company, as he called it.”

“She was one of the ‘sheros‘ who didn’t do her work for monetary gain,” White Dixon said. “It was her dedication to developing cultural arts in her community that kept her going.”

“She was a gutsy woman. She had a determined spirit. I want people to remember that she came before Misty Copeland and many of the people at the Dance Theater of Harlem. I want people to remember her, a pioneer,” White Dixon said.

Cuyjet was married to Stephen L. Cuyjet, with whom she had two sons, Stephen Jr. (MSC class of 1966) and Mark. Following her time at Maryland State, she worked as a movement therapist at Philadelphia State Hospital at Byberry.

Her impact on black dance education and the nation’s culture was recognized as her obituary detailing her contributions was published in The New York Times. The headline read: “Marion Cuyjet, 76, black ballet pioneer.”

She died Oct. 22, 1996 in Philadelphia.

By Tahja Cropper